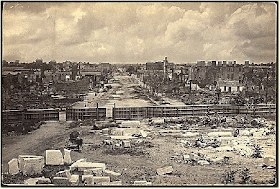

Columbia, South Carolina,

as it looked the morning after a visit

from sherman's fire fiends. "

by John T. Trowbridge

Northern

journalist

Early in the evening [of February 17] as the inhabitants,

quieted by General Sherman's assurances, were about retiring to their beds, a

rocket went up in the lower part of the city. Another in the center, and a third

in the upper part of town, succeeded. Dr. R.W. Gibbes was in the street near one

of the Federal guards, who exclaimed on seeing the signals, "My God! I pity your

city!" Mr. Goodwyn, who was mayor at the time, reports a similar remark from an

Iowa soldier. "Your city is doomed! These rockets are the signal!" Immediately

afterwards fires broke out in twenty different places.

The dwellings of

Confederate Treasury Secretary George A. Trenholm and General Wade Hampton were

among the first to burst into flames. Soldiers went from house to house,

spreading the conflagration. Fireballs, composed of cotton saturated with

turpentine, were thrown in at doors and windows. Many houses were entered and

fired by means of combustible liquids poured upon beds and clothing, ignited by

wads of burning cotton, or by matches from a soldier's pocket. The fire

department came out in force, but the hose-pipes were cut to pieces and the men

driven from the streets. At the same time universal plundering and robbery

began.

The burning of the house of R.W. Gibbes, an eminent physician,

well-known to the scientific world, was thus described to me by his

son:

"He had a guard at the front door; but some soldiers climbed in at

the rear of the house, got into the parlor, heaped together sheets, poured

turpentine over them, piled chairs on them, and set them on fire. As he

remonstrated with them, they laughed at him. The guard at the front door could

do nothing, for if he left his post, other soldiers would come in that

way.

Columbia, south carolina, as it looked the morning after a visit

from sherman's fire fiends. "The guard had a disabled foot, and my father had

dressed it for him. He appeared very grateful for the favor, and earnestly

advised my father to save all his valuables. The house was full of costly

paintings, and curiosities of art and natural history, and my father did not

know what to save and what to leave behind. He finally tied up in a bedquilt a

quantity of silver and gems. As he was going out the door the house was already

on fire behind him -- the guard said, 'Is that all you can save?" "It is all I

can carry,' said my father. 'Leave that with me,' said the guard; 'I will take

charge of it, while you go back and get another bundle.' My father thought he

was very kind. He went back for another bundles, and while he was gone, the

guard ran off on his lame leg with all the gems and silver."

The

soldiers, in their march through Georgia, and thus far into South Carolina, had

a wonderful skill in finding treasures. They had two kinds of divining-rods,"

negroes and bayonets. What the unfaithful servants of the rich failed to reveal,

the other instruments, by thorough and constant practice, were generally able to

discover. On the night of the fire, a thousand men could be seen in the yards

and gardens of Columbia by the glare of the flames, probing the earth with

bayonets.

The dismay and terror of the inhabitants can scarcely be

conceived. They had two enemies, the fire in their house and the soldiery

without. Many who attempted to bear away portions of their goods were robbed by

the way. Trunks and bundles were snatched from the hands of hurrying fugitives,

broken open, rifled, and then hurled into the flames. Ornaments were plucked

from the necks and arms of ladies, and caskets from their hands. Even children

and negroes were robbed.

Fortunately the streets of Columbia were broad,

else many of the fugitives must have perished in the flames which met them on

all sides. The exodus of homeless families, flying between walls of fire, was a

terrible and piteous spectacle. Some fled to the parks; others to the open

ground without the city; numbers sought refuge in the graveyards. Isolated and

unburned dwellings were crowded to excess with fugitives.

Three-fifths of

the city in bulk, and four-fifths in value, were destroyed. The loss of property

is estimated at thirty millions. No more respect seems to have been shown for

buildings commonly deemed sacred, than for any others. The churches were

pillaged, and afterwards burned. St. Mary's College, a Catholic institution,

shared their fate. The Catholic Convent, to which had been confided for safety

many young ladies, not nuns, and stores of treasure, was ruthlessly sacked. The

soldiers drank the sacramental wine, and profaned with fiery draughts of vulgar

whiskey the goblets of the communion services. Some went off reeling under the

weight of priestly robes, holy vessels and candlesticks.

Yet the army of

Sherman did not in its wildest orgies forget its splendid discipline. "When will

these horrors cease?" asked a lady of an officer at her house. "You will hear

the bugles at sunrise," he replied; "then they will cease, and not till then."

He prophesied truly. "At daybreak, on Saturday morning," said Gibbes, "I saw two

men galloping through the streets, blowing horns. Not a dwelling was fired after

that; immediately the town became quiet."

Some curious incidents

occurred. One man's treasure, concealed by his garden fence, escaped the

soldiers' divining-rods, but was afterwards discovered by a hitched horse pawing

the earth from the buried box. Some hidden guns had defied the most diligent

search, until a chicken, chased by a soldier ran into a hole beneath the house.

The soldier, crawling after and putting in his hand for the chicken, found the

guns.

A soldier, passing in the streets and seeing some children playing

with a beautiful little greyhound, amused himself by beating its brains out.

Some treasures were buried in cemeteries, but they did not always escape the

search of the soldiers, who showed a strong distrust of new-made

graves.

Of the desolation and horrors our army left behind it, no

description can be given. Here is a single instance: At a factory on the

Congaree, just out of Columbia, there remained for six weeks a pile of

sixty-five dead horses and mules, shot by Sherman's men. It was impossible to

bury them, all the shovels, spades, and other farming implements of the kind

having been carried off or destroyed.

Columbia must have been a beautiful

city, judging by its ruins. Many fine residences still remain on the outskirts,

but the entire heart of the city is a wilderness of crumbling walls, naked

chimneys, and trees killed by the flames. The fountains of the desolated gardens

are dry, the basins cracked; the pillars of the houses are dismantled, or

overthrown; the marble steps are broken. All these attest to the wealth and

elegance which one night of fire and orgies sufficed to destroy.