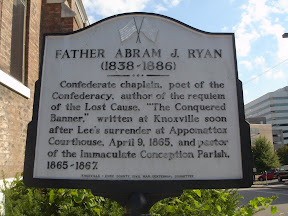

Father Abram Joseph Ryan was born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1838. His

parents were natives of Ireland. An ordained Roman Catholic priest, he

was a volunteer chaplain and seems to have been mostly associated with

the 8th Tennessee Infantry. His brother David was killed in action in

the Confederate Army during the war and this greatly affected Father

Ryan. Among his best known poems are "The Conquered Banner", "C.S.A."

and "The Sword of Robert Lee." Following the war he founded a weekly

magazine, "Banner of the South." He wrote most of his poems for this

magazine. He also wrote a book of poety that was very popular, and still

is. Father Ryan was greatly beloved as a priest as well as a poet. He

died in Kentucky and is buried in Mobile, Alabama where a park is named

in his honour (the location of the above life-size statue).

========================

VERBATIM

HOW FATHER RYANS

CONQUERED BANNER WAS RESCUED FROM OBLIVION.

Perhaps no poem ever

touched and thrilled the hearts of the people of the South as did the

"Conquered Banner," by Father Ryan. It came from the heart of

the poet at the time when the Southland stood in grief and in untold

sorrow. Though his face wore a serious and almost sad aspect, he dearly

loved to gather children about him, as he seldom spoke to older people. He

always held that little children were angels and walked with God, and that

it was a privilege for a priest to raise his hand and give spotless

childhood a blessing, writes "Aquila," in the Colorado Catholic.

It was several years ago

that "Aquila" met with a young lady from the South, who related

to him the following beautiful and touching incident in the poet's life.

The little story is as follows:

"One Christmas - I was

then a little girl," says the young lady - "I came to Father

Ryan with a bookmark, a pretty little scroll of the 'Conquered Banner,'

and begged him to accept it. I can never forget how his lips quivered as

he placed his hands upon my head and said (a little kindly remembrance

touched him so): 'Call your little sisters, and I will tell them a story

about this picture. Do you know, my children,' he said as we gathered

about his knee, 'that the "Conquered Banner" is a great poem? I

never thought it so,' he continued in that dreamy, far-off way so

peculiarly his own; 'but a poor woman who did not have much education, but

whose heart was filled with love for the South, thought so, and if it had

not been for her this poem would have been swept out of the house and

burned up, and I would never have had this pretty book-mark or this true

story to tell you.'

"'O you are going to

tell us how you came to write the "Conquered Banner!" ' I cried,

all interest and excitement.

"'Yes,' he answered,

'and I am going to tell you how a woman was the medium of its

publication.' Then a shadow passed over his faces a dreamy shadow that was

always there when he spoke of the lost cause, and he continued: 'I was in

Knoxville when the news came that Gen. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox

Court-House. It was night, and I was sitting in my room in a house where

many of the regiment of which I was chaplain were quartered, when an old

comrade came in and said to me: "All is lost, Gen. Lee has

surrendered." I looked at him. I knew by his whitened face that the

news was too true. I simply said, "Leave me," and he went out of

the room.

I bowed my head upon the table and wept long and bitterly. When

a thousand thoughts came rushing through my brain. I could not control

them. That banner was conquered; its folds must be furled, but its story

had to be told. We were very poor, my dear little children, in the days of

the war. I looked around for a piece of paper to give expression to the

thoughts that cried out within me. All that I could find was a, piece of

brown wrapping paper that lay on the table about an old pair of shoes that

a friend sent me. I seized this piece of paper and wrote the "Conquered

Banner " Then I went to bed, leaving the lines there upon the table.

The next morning the regiment was ordered away, and I thought no more of

the lines written in such sorrow and desolation of spirit on that fateful

night. What was my astonishment a few weeks later to see them appear above

my name in a Louisville paper! The poor woman who kept the house in

Knoxville had gone, as she afterward told me, into the room to throw the

piece of paper into the fire, when she saw that there was something

written upon it. she said that she sat down and cried, and, copying the

lines, she sent them to a newspaper in Louisville. And that was how the

"Conquered Banner" got into print. That is the story of this

pretty little scroll you have painted for me.'

"'When I get to be a

woman,' I said, ' I am going to write that story.'

"'Are you?' he

answered. 'Ah! it is dangerous to be a writer, especially for women; but

if you are determined, let me give you a name,' and he wrote on a piece of

paper 'Zona.' 'It is an Indian name,' he said in explanation, 'and it

means a snowbird to keep your white wings unsullied. A woman should always

be pure, and every mother should teach her boys to look upon a woman as

they would upon an altar.' "

Thus was the incident

related to me by my Southern friend. Many and many a time in the hurry and

bustle of the noisy world the words of the gentle poet-priest came back to

me, and in writing this little sketch of how it was through a woman's

thoughtfulness that the great Southern epic was given to the world I can

not refrain from repeating this little talk, which was the outgrowth of

this story, and which might prove a help and a benediction in many a

woman's life.

No inspiring column marks

the spot where the priest, patriot, and poet is sleeping, but his words

still live in the hearts of the people, and the regard, the respect, the

high esteem he held for woman bespeaks the purity of his soul.

Rest there, saddest,

tenderest, most spiritual poet heart that has sought our hearts and

breathed in them a music that the lapse of years can not still, sleep and

rest on! The visions that came to the mind of the priest as he walked

down the valley of silence, down the dim, voiceless valley alone,

are living on, for they are prayers.

Upon reading this account

of the origin of the "Conquered Banner," Mrs. J. William Jones

(wife of our Chaplain-General, and a devoted Confederate from that day in

the early spring of 1861 when she buckled her husband's armour upon him and

sent him to the front down to the present day) has written the following

lines:

He shared their every

hardship, as he did their hopes and joys,

Inspiring faith and courage as he cheered those ragged boys.

Our soldier-priest and poet stood unflinching at his post,

Till the news of Lee's surrender told the story: "All is lost."

He could bare his breast to

bayonet, be torn with shot and shell:

With victorious, tattered banner, he could bleed and die so well.

But when those dreadful words, "All lost," broke o'er him like a

flood.

His very heart seemed Weeping, and his tears all stained with blood.

How illy could he bear it

all, so sudden was the blight,

glut for the poet's genius, which filled his soul with light.

He sought in vain material his burning words to give

To future generations, and to hearts where he would live.

A crushed brown paper on the

floor served then his purpose well

For though it seemed a conquered cause, he must its story tell.

He wrote it out and fell asleep: next morn thought of it not.

New troubles filled the poet's heart his poem was forgot.

The morning dawned: that

broken priest, but soldier never

Was gone, but left, all blurred with tears that paper on the floor.

A woman, loving well our cause, found, and its folds unfurled,

The "Conquered Banner," and it floats unconquered to the world.

At last he bivouacs in

peace: no monument stands guard

To point us where the poet-priest sleeps sweetly ‘neath the sod

His glorious rhythmic poems rare a monument will stand;

He was its architect, and built both gracefully and grand:

Miller School, Va., August

9, 1897

=========

THE CONQUERED BANNER

by Abram Joseph Ryan

(1838-1886)

Furl that Banner, for 'tis weary;

Round its staff 'tis drooping dreary;

Furl it, fold it, it is best;

For there's not a man to wave it,

And there's not a sword to save it,

And there's no one left to lave it

In the blood that heroes gave it;

And its foes now scorn and brave it;

Furl it, hide it--let it rest!

Take that banner down! 'tis tattered;

Broken is its shaft and shattered;

And the valiant hosts are scattered

Over whom it floated high.

Oh! 'tis hard for us to fold it;

Hard to think there's none to hold it;

Hard that those who once unrolled it

Now must furl it with a sigh.

Furl that banner! furl it sadly!

Once ten thousands hailed it gladly.

And ten thousands wildly, madly,

Swore it should forever wave;

Swore that foeman's sword should never

Hearts like theirs entwined dissever,

Till that flag should float forever

O'er their freedom or their grave!

Furl it! for the hands that grasped it,

And the hearts that fondly clasped it,

Cold and dead are lying low;

And that Banner--it is trailing!

While around it sounds the wailing

Of its people in their woe.

For, though conquered, they adore it!

Love the cold, dead hands that bore it!

Weep for those who fell before it!

Pardon those who trailed and tore it!

But, oh! wildly they deplored it!

Now who furl and fold it so.

Furl that Banner! True, 'tis gory,

Yet 'tis wreathed around with glory,

And 'twill live in song and story,

Though its folds are in the dust;

For its fame on brightest pages,

Penned by poets and by sages,

Shall go sounding down the ages--

Furl its folds though now we must.

Furl that banner, softly, slowly!

Treat it gently--it is holy--

For it droops above the dead.

Touch it not--unfold it never,

Let it droop there, furled forever,

For its people's hopes are dead!