In

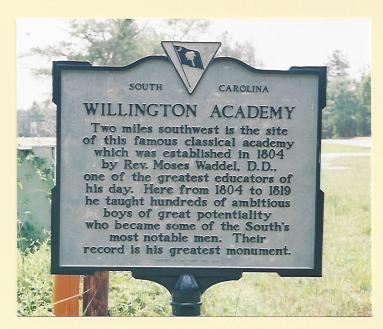

1819, Rev. Moses Waddel “was induced to give up his academy business”

and take the reins of the University of Georgia. Born in North

Carolina, educated in the ministry in Virginia and a preacher in

Georgia, he had taught young John C. Calhoun and became the first

native-born Southerner to fill the University presidency. It was not

unusual then to hear open and reasoned discussion on ending the New

England slave trade and returning Africans to their homeland.

Bernhard Thuersam, Chairman

North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission

"Unsurpassed Valor, Courage and Devotion to Liberty"

"The Official Website of the North Carolina WBTS Sesquicentennial"

Abolition Sentiment in Georgia

“Athens

[Georgia] and the Lower South at this time [1810] were in the midst of

laying the foundations of that social order and culture, beautiful and

polished yet seamy, captivating the elite Englishman and practical

Yankee who touched it, the admiration of some, the curse of some . . .

In

the excitement of the Federal Constitutional Convention, Georgia had

stood for the foreign slave trade, but she no sooner won it than she

freely flung it away. In 1819 at a banquet in Athens this toast was

drunk: “The [Foreign] Slave Trade – The scourge of Africa; the disgrace

of humanity. May it cease forever, and may the voice of peace, of

Christianity and of Civilization, be heard on the savage shores.”

At

this time the whole subject of slavery was discussed in the Georgia

papers with reason and dispassion, and in 1824 the president of the

University “heard the Senior Forensic Disputation all day on the policy

of Congress abolishing Slavery – much fatigued but amused.” Apparently

the students were doing some thinking also.

The

trustees, were, likewise not opposed to a possible disposition of

slavery, for [Rev. Robert] Finley, whom they had just elected president

of the University, had been one of the organizers of the American

Colonization Society. He was, indeed, present in Washington at its

birth and had been made one of its vice-presidents; and so vital did his

work appear to one friend that he later wrote,

“If

this colony [Liberia] should ever be formed in Africa, great injustice

will be done to Mr. Finley, if in the history of it, his name be not

mentioned as the first mover, and if some town or district in the colony

be not called Finley.” He, indeed, never lost interest in the project

to his dying day – and then it “gave consolation to his last moments.”

The

South was genuinely interested in ridding itself of this incubus,

realizing, with Henry Clay, that Negroes freed and not removed were a

greater menace than if they remained in slavery.”

(College Life in the Old South, E. Merton Coulter, UGA Press, 1983 (originally published in

1928), pp. 27-28)