Radical Republican Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts loudly encouraged war against the South in 1861, yet he worked hard purchasing the patriotism of non-Massachusetts men who would serve in his regiments. Faced with the necessity of raising 4,000 men by Lincoln’s draft and expecting a riot in Boston, he held troops in readiness and asked Secretary Stanton to institute courts martial against his enraged citizens. At Andrew’s request, Lincoln allowed him to enlist captured Africans in South Carolina for his State quota of regiments – thus keeping white Bay State men at home.

Bernhard Thuersam, www.Circa1865.com

Massachusetts Aristocracy Arms for War

“Even as conservatives were exploring the possibilities of conciliation and seeking means of influencing [president-elect] Lincoln, Massachusetts’ newly elected Governor, John Andrew, was kindling the fires of radicalism. Southern society, he declared, must be entirely reorganized, and the federal government ought to be driven to aid in the work.

There must be no “weak-kneed” measures. “I am for unflinching firmness in adhering to . . . all our principles.” “We must conquer the South,” he said, and “to do this we must bring the Northern mind to a comprehension of this necessity.” “War is in the air,” he later confessed, “and some of us breathed it.”

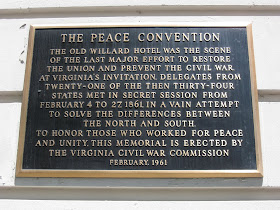

As Congress gave more attention to compromise measures, Andrew hurried to Washington to consult with congressional radicals. A Virginia congressman, John Y. Mason, swore to Andrew that never could the South be induced to rejoin a Union of which Massachusetts was a member.

Thus confirmed in his direst apprehensions, Andrew held conference, on Christmas Eve, with Senators Doolittle of Wisconsin, Trumbull of Illinois, and Sumner and Wilson of his own Massachusetts. Solemnly the radical coterie decoded that the integrity of the Union must be preserved, “though it cost a million lives.”

The Governor-elect’s impassioned and sanguinary pronouncements chilled conservative hearts in Massachusetts. Boston Brahmins were horrified and indignant; they distrusted Andrew, whom they believed to be wanting in good judgment, common sense and practical ability.

“What was apprehension about Andrew,” ruefully admitted Sam Bowles, “is now conviction.” He wobbles like an old cart – is conceited, dogmatic, and lacks breadth and tact for government.” Democrats, sickened by the radicals’ willingness to sacrifice other men’s lives, asked whether people wished to die for the radical cause.

[On his inauguration day January 1, 1861, the new governor stated that] South Carolina’s secession was an injury to the Old Bay State, which was ready to endure once more, if need be, the sacrifices it had borne during the Revolution. So saying, the newly-sworn Governor called on the legislature to arm the State for war.

The entire address, sneered the Boston Post, was a lamentable appeal to passion, combining “the narrowness of a mere lawyer, with the intenseness of a fanatic.” It was “sophomoric in style, immature in thought, wretched in argument, and small in political knowledge.”

To assist him in his work, Andrew chose four aides – carefully culled from Harvard graduates and the better families – bestowed military titles upon them, and put them to gathering steamboats, purchasing supplies and inspecting the militia. The people, [Andrew] said, must become used to the smell of gunpowder.”

(Lincoln and the War Governors, William B. Hesseltine, Alfred A. Knopf, 1948, pp. 110-112)