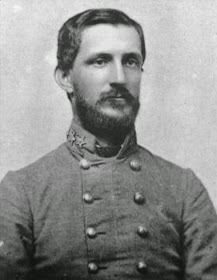

During the 1961-1965 Centennial of the War Between the States, a North Carolina History school textbook featured “the likeness of Hoke flanked by those of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.” This gives us today an idea of how prominent a man and leader this man was, though he is not as well known as other Southern generals of that period.

A Lincoln County, North Carolina native born in 1837, Robert F. Hoke was the son of Michael and Frances Hoke -- the father a North Carolina legislator and Trustee of the University of North Carolina. Four other future Confederate generals were born in Lincoln County.

Robert F. Hoke began the war as a twenty-three year-old second lieutenant -- not a West Point graduate -- and in the first fight at Bethel Church in Virginia in June 1861. He led his men in through most of the major battles of the Eastern Theater, and in less than three years he had been promoted to major-general, the youngest major-general in the Confederate army. It was said that Hoke was Lee’s choice to lead the Army of Northern Virginia should he be disabled.

While a brigadier-general in early 1864, President Jefferson Davis and Lee detached Hoke from the Virginia theatre with orders to liberate the eastern North Carolina town of Plymouth from enemy occupation.

Hoke not only forced the surrender of that enemy-fortified town, its garrison and plentiful supplies, but came very close to doing the same with nearby enemy-occupied New Bern.

In late December 1864 and Fort Fisher the anticipated target of enemy attack, Hoke was detached again from Lee’s command to reinforce and support the fort’s garrison. Arriving at Christmas, Hoke was unable to counter-attack due to numerous enemy gunboats close to shore that would enfilade his assault force.

Withdrawing to the Forks Road position a few miles south of Wilmington, he effectively stopped the enemy advance, then withdrew through Wilmington after nearby Fort Anderson fell and its garrison later routed at the Town Creek battle.

After the enemy advance across the river forced Hoke to withdraw from Forks Road, he and his men followed the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad northward, stopping at the north bank of Rockfish Creek, one mile south of Duplin Crossroads, today’s Wallace. There Hoke established defensive works flanking the railroad trestle at Rockfish Creek; Hoke had wisely taken all rolling stock in Wilmington with him which rendered the line virtually unusable to the enemy.

Remaining at Duplin Roads until March 5th, Hoke was ordered to Kinston to stop an enemy advance from New Bern, and there his men saw battle at Wyse’s Forks on March 8th. Hoke’s men nearly destroyed an enemy regiment there, captured three artillery pieces and 1500 enemy soldiers.

After continued fighting against a steadily increasing enemy army, Hoke was ordered to Smithfield on March 11th along with “the beardless boys of the NC Junior Reserves.”

They were all utilized in Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s strategic trap set at nearby Bentonville which awaited the 65,000-man enemy army approaching from Averasborough.

Here Gen. Hoke’s men distinguished themselves on the 19 and 20th despite suffering high casualties

the first day;

the second day Hoke repulsed the enemy’s repeated attacks “and offered a deadly hailstorm of bullets. Their ranks were mowed down like wheat before the scythe . . . .” Gen. Johnston, after hearing of the attack on Hoke’s line said, “I know of no brigade in the Southern army I would sooner they attack.”

It is said that the enemy was driven back so completely that Hoke’s medical personnel brought in enemy wounded to be cared for.

Though not the grand victory hoped for, Johnston’s 20,000-man army at Bentonville – 4000 of them Hoke’s men -- had battled to a stalemate against a total enemy force of over 60,000.

At Smithfield on April 4th, Hoke’s men joined the rest of Johnston’s army in grand review and attended by many of the area’s civilians. Young Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Clark of the Junior Reserves, a future North Carolina Supreme Court judge, wrote his mother of the patriotism still evident: “I intend to stand by the cause while a banner floats to tell where Freedom and freedom’s sons still support her cause.”

After the capitulation by Johnston near Greensboro, Hoke addressed a farewell to his men on May 1st.

“Soldiers, your past is full of glory! Treasure it in your hearts, remember each gory battlefield, each day of victory, each bleeding comrade. You have yielded to overwhelming numbers, not superior valor.

You are paroled prisoners, not slaves. The love of liberty, which led you into this contest, burns as brightly in your hearts as ever. Cherish it. Associate it with the history of your past. Transmit it to your children.

Teach them the rights of freedom, and teach them to maintain them.

Teach them the proudest day in all your proud career was that on which you enlisted as Southern soldiers, entering that holy brotherhood whose ties are now sealed by the blood of your compatriots who have fallen.

But it is all over now. Yet, the sad, dark veil of defeat is over us, fear not the future, but meet it with manly hearts. You carry to your homes the heartfelt wishes of your General for your prosperity.

My comrades, farewell.

North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

“Unsurpassed Valor, Courage and Devotion to Liberty”

www.ncwbts150.com

Jenn Grover

Jenn Grover