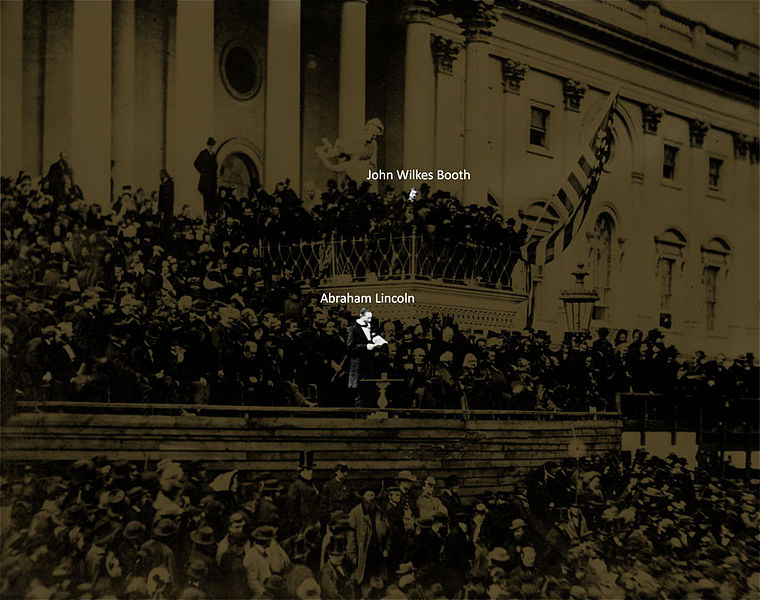

Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address.

In his 1899 “Life of Lincoln” Norman Hapgood wrote that “Charles A. Dana testifies that the whole power of the [United States] War Department was used to secure Lincoln’s re-election on 1864. There is no doubt that this is true. Purists may turn pale at such things, but the world wants no prettified portrait of Mr. Lincoln’s Jesuitical ability to use the fox’s skin when the lion’s proves too short and that was one part of his enormous value.” The military was depended upon to deliver the soldier vote and ensure civilian ballots for the Republicans.

Bernhard Thuersam, www.Circa1865.com The Great American Political Divide

Events Leading to Lincoln’s Second Election

“Lincoln’s second election was largely committed to the War and Navy Departments of the Federal government, he having been nominated by the same radical Republican Party . . . that nominated him at Chicago in 1860 . . .

Lincoln made criticism of his administration treason triable by court-martial, and United States soldiers ruled at the polls. General B.F. Butler’s book gives full particulars of the large force with which he controlled completely the voters of New York City; and McClure’s book, “Our Presidents,” tells “how necessary the army vote was, and was secured”; and Ida Tarbell says: “It was declared that Lincoln had been guilty of all the abuses of a military dictatorship.”

Lincoln’s [military] success was not won by the North, for a large part of the people were against Lincoln’s policy of coercion. So, seeing voluntary enlistments ceasing, and the draft unpopular, by offering large bounties and other inducements, Lincoln secured recruits, as follows: 176,800 Germans, 144,200 Irish, 99,000 English and British-Americans, 74,000 other foreigners, 186,017 Negroes, and from the border States 344,190, making a grand total of 1,151,660 men.

Therefore, had Lincoln depended on Northern volunteers to extricate himself from the desperate toils in which he was involved by his own willful and criminal war policy, he would surely have lost out; for, in 1864, there was great reaction against him.

Finally, let it not be forgotten, that [the] principle of government by the consent of the people [for which the South fought] was the rock on which our fathers of 1776 had built the “new and more perfect” Union of States; and later, was the fundamental principle of the Union of the Southern Confederacy . . .”

(Cornelius B. Hite, Washington, DC, Confederate Veteran, July, 1926, excerpts, pp. 248-249)