Mike

Scruggs

Several years ago I wrote

a series of articles entitled “The Hanging of Mary Surratt.” Those

articles were published in the North Carolina Tribune Papers and South

Carolina’s Times-Examiner and

held considerable reader attention for months. They were later incorporated into

my book, The Un-Civil War: Shattering the

Historical Myths, published by Universal Media in

2011.

Mary Surratt was

an attractive, dark-haired widow and boarding house proprietor, who was one of

four alleged conspirators in the Lincoln assassination hanged on July 7, 1865.

At forty-two, she was the first woman ever to be executed by the United States

government.

No nation can

long endure without a strong sense of patriotism, and Americans, like most of

the more prominent peoples of mankind, have a strong tendency to whitewash

history in order to protect the purity of their national narrative. It is more

pleasant to remember and teach an unblemished historical narrative of national

virtue. The blemishes of such national narratives tend to be swept under the

rug, and lifting up the edges of that rug to inspect the blemishes is not always

welcome. The defenders of an unblemished national narrative often react harshly

and go to great lengths of academic and political cover-up to defend strongly

entrenched but fallacious interpretations of history. Such is the case

with the trial and execution of Marry Surratt.

The hanging of

Mary Surratt was not a triumph of justice. It was a disgraceful political and

judicial atrocity that still stains the national conscience and mars the

American ideal of justice. There are still many who feel compelled to defend her

hanging lest we have to look directly into unwelcome truth. But genuine

patriotism is undermined when truth becomes subservient to propaganda and

political ambitions. Truth and genuine love of country are inseparable.

Patriotism without truth is a monstrous imposter.

The Lincoln

assassination conspiracy trial was marked by judicial despotism, suborned

perjury, bribery, and the intimidation and torture of witnesses and defendants.

The investigation, prosecution, trial, and sentences were all managed by the

U.S. War Department under its politically ambitious and ruthless Secretary,

Edwin Stanton, aided by his Chief of Detectives, Col. Lafayette

Baker.

Stanton is often

portrayed as one of Lincoln’s “team of rivals” who ultimately became his most

supportive, loyal, and sympathetic cabinet member. Stanton often did seem to

work well with Lincoln as part of a “good cop-bad cop” team in making stressful

political and military decisions. Stanton often played the “bad cop” who allowed

the President to maintain a more kindly public face in often-harsh dealings with

Northern Democrat opposition and what became a total war policy against Southern

civilians. The reality was that Lincoln was more kindly in disposition than

Stanton, whose ruthlessness often manifested itself with other cabinet members

and independent actions unknown to the President.

One of the

Lincoln cabinet members I have come to admire was Secretary of the Navy Gideon

Welles, who finally felt compelled to privately convey to Lincoln the ugly truth

of Stanton’s devious and “back-stabbing’ nature. Stanton had well-earned the

“back-stabbing” reputation with other cabinet members and several Union General

officers.

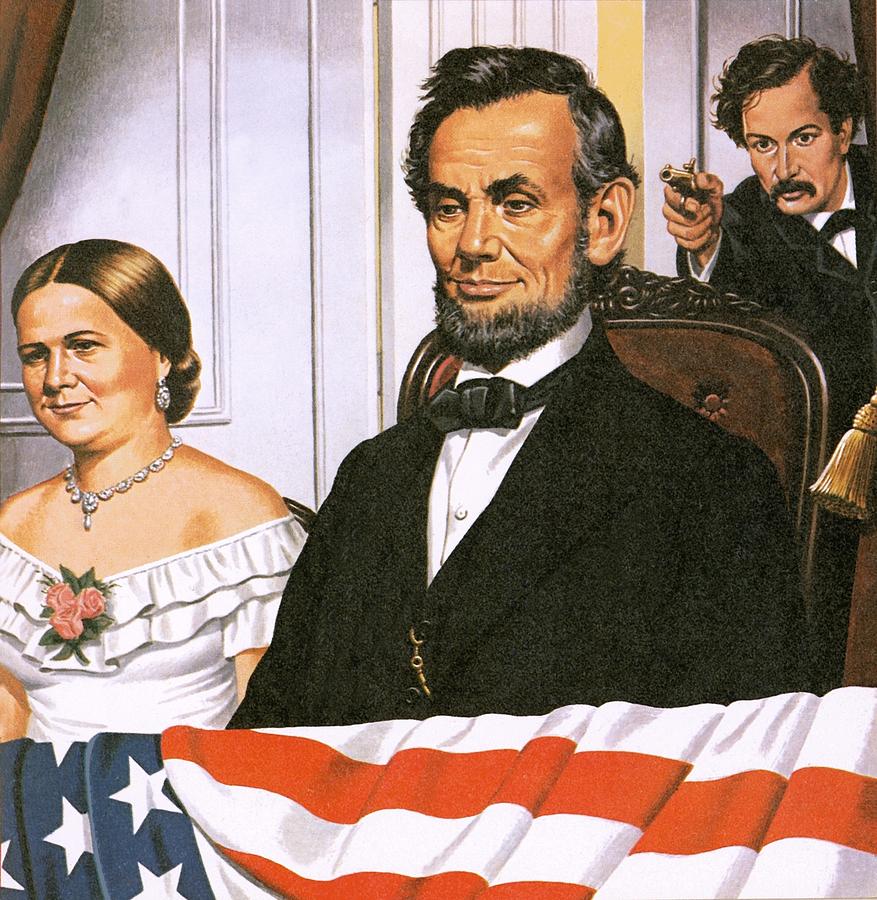

Stanton and the

fifteen or so leading “Radical Republicans” in Congress were anxious to connect

Confederate President Jefferson Davis with John Wilkes Booth’s shooting of

Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington on April 14, 1865. Stanton had

orchestrated an attempted assassination of Davis in February 1864. Davis,

however, publicly and privately decried assassination of political leaders as a

strategy of war. No one who is thoroughly familiar with Davis’s highly ethical

character places any credence on such an accusation. I also believe that

Vice President Andrew Johnson was an unlikely assassination conspirator. He was

very anti-secession but very pro-Constitution. He had a drinking problem, but

had sterling qualities of character, which eventually showed though his faults.

As the former Tennessee Democrat’s passion for the Constitution and renewing

compassion for the Southern people began to show, Stanton and the Radicals began

to hate him and would soon attempt to impeach him.

I also place no

credibility in theories that someone other than John Wilkes Booth fatally

wounded Abraham Lincoln on the evening of April 14, 1865. Booth’s first plan was

to capture Lincoln and hold him ransom in pursuit of the release of Confederate

prisoners of war and possibly a negotiated peace. Booth’s own diary indicated he

did not decide to kill Lincoln until April 13. Stanton withheld that diary and

information from the Military Court.

Lincoln’s plan

for a relatively benign reconstruction of the Southern States after the War was

a concern to Stanton and the Radical Republicans. They were determined to wreak

vengeance and continued economic exploitation on the formerly seceded states.

More importantly, Lincoln’s relatively mild reconstruction plan risked the

return of a Democrat Congressional majority. The Radical Republicans were not

about to hand power back to a Democrat majority.

Readers

should bear in mind that the Republican and Democrat parties were quite

different from their modern descendents. Democrat and “conservative” were

virtual synonyms then. Democrats, North and South, were particularly strong on

preserving limited Constitutional government and States Rights. The

Republicans varied from conservative to radical, but were largely a big

business-big government dominated party. The Radical Republicans were the most

unapologetic and ruthless advocates of using big government to profit big

business and big business funding for successful political campaigns. They

favored harsh and exploitive reconstruction that disenfranchised Confederate

veterans and maintained Republican power in the South through Northern

“carpetbaggers” and newly franchised Republican former

slaves.

Secretary

Stanton’s Chief Detective, Lafayette Baker, on taking charge of the pursuit of

Lincoln’s assassins gave official orders “to extort confessions and procure

testimony to establish conspiracy…by promises, rewards, threats, deceit, force,

or any other effectual means.”

Why did Stanton go so far

in breaking all the rules of honest investigations and fair trials to

hang Mary Surratt? Why did he persuade General Grant to reject the

President’s invitation to attend the theater with him on April 14? There are

more peculiar coincidences and unanswered questions.