Though

the author below cites Tennessee’s 1881 legislation as the first of the

“Jim Crow” type, New York in 1821 enfranchised all adult white male

citizens, but kept black men in a politically subordinate caste with a

$250 property-holding requirement for voting. Leading this initiative

was future president Martin Van Buren who argued that “democracy only

made sense with racial exclusion.” Van Buren ran for president again in

1848 on the Free Soil party ticket, which desired white racial

exclusivity in the western territories.

Bernhard Thuersam, Director

Cape Fear Historical Institute

"Documenting Cape Fear People, Places and History"

“Jim Crow” Law Origins:

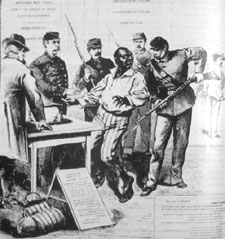

“The

practice of requiring by legislative enactment that Negroes use

railroad coaches or compartments separate from this for whites, commonly

referred to as “Jim Crow” legislation, did not become general in the

South until the closing decade of the nineteenth century.

Earlier,

however, in 1881, the legislature of Tennessee enacted a law requiring

railroads to provide separate cars or compartments for the use of

Negroes. By this abortive statute – for so it proved to be – Tennessee

acquired a somewhat undeserved notoriety, at least in one college

textbook, as the originator of “Jim Crow” legislation.

Moreover,

the purpose of this law and the circumstances surrounding its enactment

were strikingly different from what is generally believed to be the

origin of this type of discriminatory legislation. It is often assumed

that prior to the passage of the “Jim Crow” laws no effective racial

discrimination existed on railroad trains.

The

alleged “Jim Crow” law of 1881 was enacted by a legislature in which

one house was controlled by the Republican party and which included four

Negro members. Only two Negro members voted against the measure; the

other two did not vote.

The

bill was signed without hesitation by the first Republican governor of

the State elected after the overthrow of the Radical [Republican]

regime. The apparent anomaly of Republican support is explained by the

fact that the bill was considered by white [legislature] members to be a

concession to Negroes – a consolation prize designed to assuage

somewhat the sting caused by the failure of the four Negro legislators

to secure the repeal of a more seriously discriminatory statute passed

in 1875.

[An

1880 Federal circuit court reviewed a case involving] a Negro woman,

alleged to have been a “notorious and public courtesan, addicted to the

use of profane language and offensive conduct in public places.” She had

been forced to move from the ladies’ car to the smoking car, which was

crowded with passengers, mostly immigrants traveling on cheap rates.

[The railroad company] based its case on the reputation rather than the

color of the plaintiff.

With

regard to trains carrying three or more passenger cars it appears that

the railroads attempted, at least, to pay lip service to the Tennessee

law…..they usually provided what was called the “colored” first class

car, to which Negroes of both sexes with first class tickets were

assigned but which was also available for the use of white persons..

[Though] not exclusively for the use of Negroes, they were sometimes

referred to as “Jim Crow” cars.

The

innovation of the modern “Jim Crow” car was not the result of the

Tennessee law of 1881 but of Supreme Court approval of a Mississippi

statute of March 2, 1888 [requiring separate but equal facilities].

[The Court held the Mississippi law as constitutional, with Kentuckian

and Justice] John M. Harlan dissenting, on March 3, 1890 . . .

[deciding] that the opinion of the Mississippi Supreme Court that the

law applied only to intrastate commerce must be accepted as conclusive.

It also held that the law was no more a burden on interstate commerce

than requiring certain accommodations at depots or enforcing stops at

street crossings.

(The

Origin of the First “Jim Crow” Law, Stanley J. Folmsbee, Journal of

Southern History, Volume XV, Number 2, May, 1949, pp. 235-237; 243-244)