One of the results of 1865 was the establishment of a protected class of citizens of the now-consolidated United States; prior to 1865 the States were the locus of who and what a citizen of their sovereign domains were, and what qualifications had to be met in order to vote. The ongoing reconstruction of the South after WWII saw the central government assume control of education to enforce equalities other than political for its protected class, and the predictable chaos has resulted.

Bernhard Thuersam, www.circa1865.com

Achieving Proper Chromatography in Public Schools:

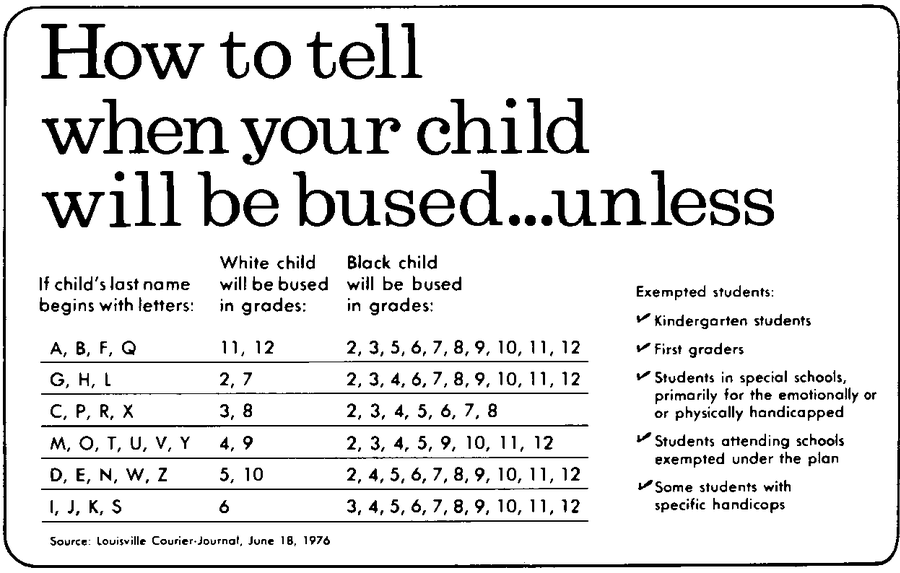

“No one has yet constructively and pragmatically defined what “integration” in the schools requires. Enough survey work has been done to show that Negro parents, like white parents, are more interested in the quality of education than in the chromatic proportions of the classroom. Yet in every city so much emotion is spent weighing the numbers, the percentages, the admixture of black and white, that Negro leaders have convinced far too many of their own people that Negroes sitting together in one classroom retard each other’s education.

In cities like Washington DC, where 80% of children in public schools are Negro, or areas like Manhattan, where 69% are Negro and Puerto Rican, “integration” could be achieved only by the most mechanical and arbitrary importation of white children from distant areas.

So in the name of “integration” some Negro leaders, notable in Los Angeles and New York, are demanding that white children be transported into Negro slums to achieve proper chromatography. Few Negro leaders in New York dare denounce the idea publicly for fear they will be blasted by others of their race for being against “integration.” Meanwhile white parents can be tormented by a magnificently emotional appeal: “Integration means your kids will be forced on buses and shipped to Harlem with all those illegitimate and backward kids.”

The kind of confusion set up by the word “integration” as applied to education is best reflected in a conversation with a bitter young Negro student leader in Chicago who began by listing as his No. 1 demand of American society ”separate but superior education for Negroes – if we could get it.”

Then, after increasingly emotional talk for an hour, he took up the matter of cross-busing white children into Negro districts and said: “The white kids got to pay for what their parents did to us. Even at the age of 6, they got to pay – because they’re going to pay one way or the other. Besides, it will be good for them.”

(Power Structure, Integration, Militancy, Freedom Now!, Theodore H. White, Life Magazine, November 29, 1963, pp. 78-80)

Achieving Proper Chromatography in Public Schools:

“No one has yet constructively and pragmatically defined what “integration” in the schools requires. Enough survey work has been done to show that Negro parents, like white parents, are more interested in the quality of education than in the chromatic proportions of the classroom. Yet in every city so much emotion is spent weighing the numbers, the percentages, the admixture of black and white, that Negro leaders have convinced far too many of their own people that Negroes sitting together in one classroom retard each other’s education.

In cities like Washington DC, where 80% of children in public schools are Negro, or areas like Manhattan, where 69% are Negro and Puerto Rican, “integration” could be achieved only by the most mechanical and arbitrary importation of white children from distant areas.

So in the name of “integration” some Negro leaders, notable in Los Angeles and New York, are demanding that white children be transported into Negro slums to achieve proper chromatography. Few Negro leaders in New York dare denounce the idea publicly for fear they will be blasted by others of their race for being against “integration.” Meanwhile white parents can be tormented by a magnificently emotional appeal: “Integration means your kids will be forced on buses and shipped to Harlem with all those illegitimate and backward kids.”

The kind of confusion set up by the word “integration” as applied to education is best reflected in a conversation with a bitter young Negro student leader in Chicago who began by listing as his No. 1 demand of American society ”separate but superior education for Negroes – if we could get it.”

Then, after increasingly emotional talk for an hour, he took up the matter of cross-busing white children into Negro districts and said: “The white kids got to pay for what their parents did to us. Even at the age of 6, they got to pay – because they’re going to pay one way or the other. Besides, it will be good for them.”

(Power Structure, Integration, Militancy, Freedom Now!, Theodore H. White, Life Magazine, November 29, 1963, pp. 78-80)