The last sentence says it all.

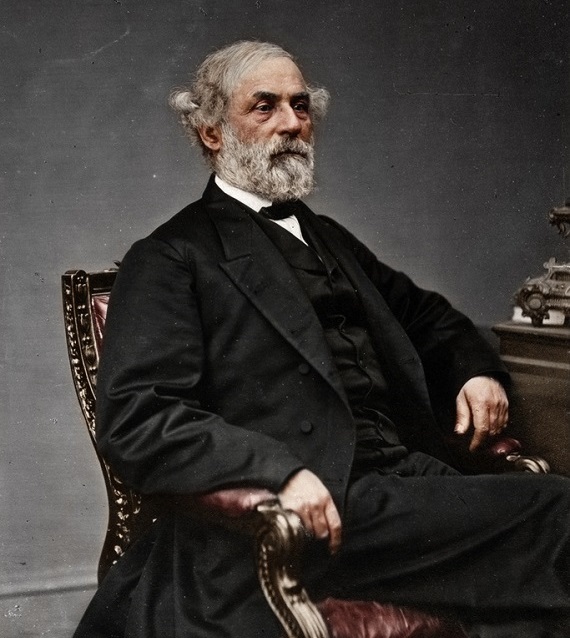

When we had registered my brother asked the General for a copy of his rules. General Lee said to him, “Young gentleman, we have no printed rules. We have but one rule here, and it is that every student must be a gentleman.” I did not, until after years, fully realize the comprehensiveness of his remark, and how completely it covered every essential rule that should govern the conduct and intercourse of men. I do not know that I could define the impression that General Lee left on my mind that morning, for I was so disappointed at not seeing the warrior that my imagination had pictured, that my mind was left in a confused state of inquiry as to whether he was the man whose fame had filled the world. He was so gentle, kind, and almost motherly, in his bearing, that I thought there must be some mistake about it. At first glance General Lee’s countenance was stern, but the moment his eye met that of his entering guest it beamed with a kindness that at once established easy and friendly relations, but not familiar. The impression he made on me was, that he was never familiar with any man.

I saw General Lee every day during the session in chapel (for he never missed a morning service) and passing through the campus to and from his home to his office. He rarely spoke to any one—occasionally would say something to one of the boys as he passed, but never more than a word. After the first morning in his office he never spoke to me but once. He stopped me one morning as I was passing his front gate and asked howl was getting on with my studies. I replied to his inquiry, and that was the end of the conversation. He seemed to avoid contact with men, and the impression which he made on me, seeing him every day, and which has since clung to me, strengthening the impression then made, was, that he was bowed down with a broken heart. I never saw a sadder expression than General Lee carried during the entire time I was there. It looked as if the sorrow of a whole nation had been collected in his countenance, and as if he was bearing the grief of his whole people. It never left his face, but was ever there to keep company with the kindly smile. He impressed me as being the most modest man I ever saw in his contact with men. History records how modestly he wore his honors, but I refer to the characteristic in another sense. I dare say no man ever offered to relate a story of questionable delicacy in his presence. His very bearing and presence produced an atmosphere of purity that would have repelled the attempt. As for any thing like publicity, notoriety or display, it was absolutely painful to him. Colonel Ruff, the old gentleman with whom I boarded, told me an anecdote about him that I think worth preserving. General Lee brought with him to Lexington the old iron-gray horse that he rode during the war. A few days after he had been there he road up Main street on his old war horse, and as he passed up the street the citizens cheered him. After passing the ordeal he hurried back to his home near the college. … He was incapable of affectation. The demonstration was simply offensive to his innate modesty, and doubtless awakened the memories of the past that seemed to weigh continually on his heart. The old iron-gray horse was the privileged character at General Lee’s home. He was permitted to remain in the front yard where the grass was greenest and freshest, notwithstanding the flowers and shrubbery. General Lee was more demonstrative toward that old companion in battle than seemed to be in his nature in his intercourse with men.

I have often seen him, as he would enter his front gate, leave the walk, approach the old horse, and caress him for a minute or two before entering his front door, as though they bore a common grief in their memory of the past.