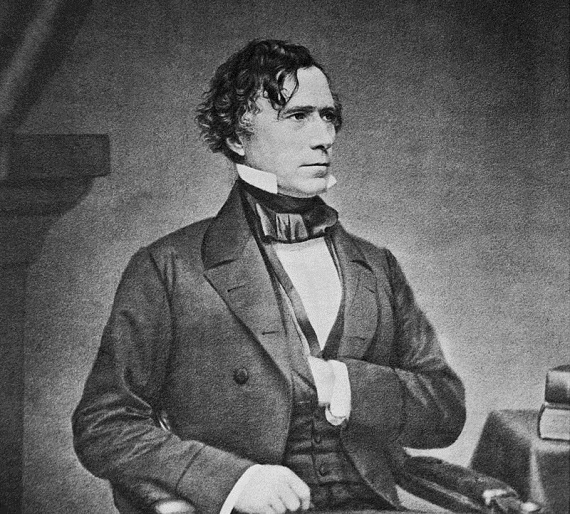

On the stump in New Boston, New Hampshire in early January 1852, Franklin Pierce gave a long oration during which free-soil hecklers forced him to address his ideas on slavery. “He was not in favor of it,” the Concord Independent Democrat reported. “He had never seen a slave without being sick at heart. Slavery was contrary to the Constitution in some respects, and a blot upon the nation.”

Pierce also scorned the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which trumped various state-level “personal liberty laws” that weakened the original 1793 fugitive slave law. “[H]e said he did not like the law—he loathed it—it was opposed to humanity, and moral right.” Despite all this, the Constitution was a compromise, and if it had not been for the slavery provisions it would not have been enacted at all.

He may not like slavery or the fugitive slave laws, but the Constitution recognized them, and the benefits of the Constitution far out-weighed any other issue or concern. Disliking slavery yet fearful for national survival outside the Constitution—this was Pierce’s great dilemma and it makes a useful starting point to reassess his ideas, and those of conservative Northern Democrats, on the limits of abolition and protest.[1]

More @ The Abbeville Institute

No comments:

Post a Comment